The Strange and Dangerous World of America’s Big Cat People

A headline-grabbing murder-for-hire plot helped expose the dark side of exotic animal ownership in the U.S. Is there now enough momentum to reform the industry?

by: Rachel Nuwer

March 2020

It’s a gloomy April afternoon in rural Oklahoma, and I’m sitting on the floor of a fluorescent-lit room at a roadside zoo with Nova, a 12-week-old tiliger. She looks like a tiger cub, but she’s actually a crossbreed, an unnatural combination of a tiger father and a mother born of a tiger and a lion. That unique genetic makeup places a higher price tag on cubs like Nova, and makes it easier, legally speaking, to abuse and exploit them. Endangered species protections don’t apply to artificial breeds such as tiligers. Hybridization, however, has done nothing to quell Nova’s predatory instincts. For the umpteenth time during the past six minutes, she lunges at my face, claws splayed and mouth ajar — only to be halted mid-leap as her handler jerks her harness. Unphased, Nova gets right back to pouncing.

With her dusty blue eyes, sherbet-colored paws, and prominent black stripes, Nova is adorable. But she also weighs 30 pounds and has teeth like a Doberman’s and claws the size of jumbo shrimp. Nova’s handler, a woman with long brown hair who tells me she recently retired from her IT job at a South Dakota bank to live out her dream of working with exotic cats, scolds the rambunctious tiliger in a goo-goo-ga-ga voice: “Nooooo, nooooo, you calms down!” Nova is teething, the handler explains, so she just wants something to chew on. The handler reaches for one of the tatty stuffed animals strewn around the room — a substitute, I guess, for my limbs. In that moment of distraction, Nova lunges. She lands her mark, chomping into the bicep of my producer, Graham Lee Brewer.

“Ooo, she got me!” Lee Brewer grimaces as he attempts to pull away from the determined predator. Nova’s handler has to pry the tiliger’s jaws open to detach her. After the incident, the woman conveniently checks her watch: “OK, you guys, time is up!”

I paid $80 for the pleasure of spending 12 minutes with Nova, but I’m glad the experience, billed as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, is over. On our way out, we pass more than a dozen adult tigers yowling and pacing cages the size of small classrooms. Nearby signs solicit donations. You are their only hope. Sponsor a cabin or compound today! In the safety of our car, Lee Brewer rolls up his sleeve, exposing a swollen red welt. “Look at my gnarly tiger bite,” he chuckles. “I tried to play it off but I was like, this fuckin’ hurts!”

It’s not the first time I’ve seen this world up-close; I spent the better part of eight years investigating wildlife trafficking around the world. During my travels, I visited farms in China and Laos where tigers are raised like pigs, examined traditional medicine in Vietnam, ate what I was told was tiger bone “cake,” and tracked some of the world’s last remaining wild tigers in India. Almost everywhere I went, tigers were suffering and their numbers were on the decline because of human behavior. Until recently, though, I had no idea the United States was part of the problem.

Within a few weeks of my visit, Nova will be far too big and dangerous for overpriced playtime sessions. Cats like her are most likely confined to one of those cramped cages my producer and I passed leaving the zoo, where they spend the rest of their life being speed-bred to crank out more adorable cubs. Or Nova might be sold to another breeder, or to someone who wants to keep her as a pet. Although no one tracks big cat ownership in the U.S., it’s estimated that there are likely more pet tigers in America than there are left in the wild. What’s more, depending on the species of cat, federal oversight is either limited or nonexistent. In some states, it’s easier to buy a lion — a 400-pound predatory killer — than it is to get a dog.

Animal rights activists have been pushing for decades to curb big cat ownership in this country, arguing that the industry is cruel, dangerous, and detrimental to conservation of cats in the wild. Now, reform appears within reach. The movement owes its momentum to, of all things, a murder-for-hire plot gone terribly awry. You might have seen the headlines in the Washington Post and New York magazine: Joe Exotic, a self-described “gay, gun-carrying redneck with a mullet,” among the largest tiger owners and breeders in the U.S., charged with conspiring to commit murder for hire. At its height, Joe’s zoo in Wynnewood, Oklahoma, which is where I visited Nova, housed more than 200 big cats, including lion-tiger hybrids, as well as about 60 other species, everything from lemurs to owls to giraffes. Joe even acquired a pair of alligators he claimed were once owned by Michael Jackson. Still, as one local told me, “The animals weren’t the entertainment. Joe was the entertainment.”

Last year, an Oklahoma City jury convicted Joe, whose legal name is Joseph Maldonado-Passage, of the murder-for-hire plots against a Florida activist and sanctuary owner named Carole Baskin. For Joe, Baskin had become something of an arch tiger rival. The news coverage mostly focused on Joe’s outlandish personality and the details of his decade-long feud with Baskin. But the jury also found Joe guilty of 17 wildlife crimes, including illegally killing five tigers and trafficking tigers across state lines — marking the first significant conviction of a tiger criminal in an American courtroom. “This verdict sends a shot across the bow to other roadside zoos who are playing fast and loose with federal regulations,” said Carney Anne Nasser, director of the animal welfare clinic at Michigan State University College of Law.

In other words, the bad boy of the big cat world might have inadvertently contributed to cleaning up the dirty industry he helped build and then exploited for much of his adult life.

Simba, a Bengal tiger, was sent to an animal sanctuary, Big Cat Rescue, in Tampa, Florida. (Matias J. Ocner/Miami Herald via AP)

* * *

Big cats are easier to find than you might think. I recently struck up a conversation with the chef at my favorite sushi joint in New York City. He asked what I’d been working on, and I filled him in on a bit of the Joe Exotic story and the big cat trade. To my surprise, he nodded along knowingly: “Oh yeah, a buddy of mine just got a serval!” Celebrity culture is another hot spot for exotic animal ownership. This past fall, Justin Bieber reportedly spent $35,000 on two savannah cats and created a dedicated Instagram page that quickly amassed more than 500,000 followers. When PETA criticized Bieber’s new pet choice, he posted a statement on his Instagram story telling the nonprofit group to “suck it” and “focus on real problems.”

Shopping for an unconventional animal used to mean scanning the classified sections of newspapers or fliers on the cluttered billboards at grocery stores and gas stations. But those analog methods of sale have long since given way to people hawking large cats in ways that are now more traditionally modern: closed Facebook groups and exotic pet websites. Getting an ocelot or a cheetah can be as easy as sending a DM or text, agreeing on a price, and setting a pick-up date. Depending on what state you live in, owning one of these animals might be entirely legal. And even if it’s not, there’s almost always a way to sidestep the rules, which can be confusing and are rarely enforced.

Save for a handful of regulations pertaining to animals listed in the Endangered Species Act (ESA), there’s almost no oversight of big cat ownership by the federal government. The Animal Welfare Act is supposed to ensure humane treatment of big cats and other captive animals, but the inspectors are overworked and many of the rules are weak, vague, or both. Although the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) does technically require a permit to sell endangered species such as tigers, lions, leopards, or jaguars across state lines, unscrupulous sellers and buyers often don’t want to bother with permits and deal in untraceable cash payments. At trial, one buyer even testified to participating in sales marked as “donations.” Joe Exotic used this tactic for years to evade the gaze of law enforcement. He wasn’t the only one. At Joe’s trial, that same tiger owner testified: “Everybody marks donation.”

Same goes for regulations at the state level: Loopholes abound in the legislative patchwork governing big cat ownership. “There’s lots of ways tigers have been technically regulated on paper but in practice, not so much,” Nasser said. Roughly two thirds of states have some sort of regulations prohibiting private big cat ownership as pets. In 10 states, anyone can own a lion or tiger as long as they pay as little as $30 for a license from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Four states — North Carolina, Wisconsin, Nevada, and Oklahoma — have no laws on the books at all.

Rules aside, very few people, no matter how well-intentioned, are prepared to own one of the world’s largest, deadliest predators. “Everybody wants a tiger cub, but nobody wants a tiger,” said Tim Harrison, a retired Ohio police officer and first responder who specialized in exotic creatures. These days, Harrison runs Outreach for Animals, a nonprofit that advocates responsible exotic pet ownership and trains emergency personnel to safely deal with animal-related crises. Harrison used to be a big cat owner himself, before realizing his mistake. “I was on the dark side,” he said, “thinking I was doing the right thing.”

Many big cat owners are subjected to what Harrison describes as a “baptism in reality,” learning firsthand that these adult cats are expensive and dangerous. “A big cat is like a walking, thinking IED,” he said. “You don’t know when that thing’s going to go off.” One of the most famous incidents took place in 2003 at a live performance by the popular entertainment act Siegfried and Roy. One of the duo’s iconic white tigers, Mantacore, knocked down Roy Horn, grabbed him by the neck, and dragged him away. First responders rushed Horn to the hospital in critical condition. He survived but only returned to the stage once more years later. Defenders of the popular act contended that Horn suffered a stroke mid-act and Mantacore was just trying to help him, but Harrison disagreed. He argued on national television that Mantacore had intended to kill Roy, and that Roy had brought this upon himself: He’d disrespected the largest predatory cat in the world by forcing the animal to do magic tricks.

No agency tracks the number of people attacked and killed by captive big cats. According to a database of incidents compiled by the Humane Society of the United States, 24 people have died and 294 have been injured in the U.S. since 1990. Those figures likely only represent a fraction of the real numbers. Not every case makes the news, and the people involved in these incidents don’t always divulge the true cause of injury. In 1999, when a family’s pet tiger killed a 10-year-old girl in Texas, the victim’s mother initially told emergency dispatchers that her daughter had cut her neck by falling off a fence. (She’d later testify she did not recall making the phone call.) In 2003, a man in New York City visited the hospital for a severe wound on his arm and leg; he claimed to have been bitten by a pit bull — not by Ming, the 400-pound tiger he had holed up in his Harlem apartment.

Big cats can threaten more than just their owners. The most infamous example occurred in 2011, when exotic animal owner Terry Thompson opened the doors to almost all of his pets’ cages before shooting himself. In what came to be known as the Zanesville massacre, law enforcement officers had to hunt and kill 18 tigers, 17 lions, and three mountain lions, as well as bears, a baboon, and wolves. “It was like Jumanji in real life,” said Harrison, who was one of the two dozen or so officers who responded to the incident. Many of the people who responded to the call that day suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, Harrison claimed. They had no choice but to kill the animals, then they faced virulent public backlash for doing so.

Zanesville is an extreme example, but it’s not the only case of exotics turned loose. One problem is there’s a lack of places equipped to take in these animals — even zoos don’t want them. Since starring in a 2011 documentary The Elephant in the Living Room, about exotic cat ownership, Harrison gets about 30 calls a year from people desperate to find a new home for their lions or tigers. With few options, some people donate their cats to shady facilities that use them for breeding. Others abandon them. The New York Times recently reported that a woman looking for a place to smoke a joint stumbled upon a caged tiger in a vacant home in Houston. Unsurprisingly, the owner did not immediately come forward to claim the tiger, but she was later arrested and charged with one misdemeanor count of cruelty to a nonlivestock animal.

A sign warning motorists that exotic animals are on the loose rests on I-70 Wednesday, Oct. 19, 2011, near Zanesville, Ohio. (AP Photo/Tony Dejak)

* * *

As a boy, Joe Exotic raised pigeons and captured porcupines, racoons, and baby antelope at his childhood homes in Kansas and rural Wyoming. But it was the death of his older brother, Garold Wayne, in a car accident in 1997, that precipitated Joe’s entrance into the tiger business: Joe convinced his parents to use the roughly $140,000 settlement they received to open a wildlife rescue center.

Before Joe and his parents had completed the first cages at the GW Exotic Animal Memorial Foundation in 1999, someone dropped off an unwanted mountain lion and black bear. Soon after, they received a call about two tigers, a black leopard, and a mountain lion found in a backyard. Joe set out with a horse trailer and tranquilizers to collect the animals, which were skinny and malnourished. When Joe spoke to me this spring on the phone from a county jail in Oklahoma, he told me there was an excitement about the uncertainty and possibility of those early days. “I had no intention of being Joe Exotic or the Tiger King or anything like that,” said Joe, who came up with the “Tiger King” moniker because people struggled to pronounce his original surname, Schreibvogel. “But I never said no to a rescue.”

Pretty soon, Joe started breeding his own tigers. He bred some 400 big cats over the years. He sold the animals to buyers on both coasts for as much as $5,000 each. By the mid-2000s, Joe had become one of the largest exotic animal operators in the country. He owned dozens of species and put together a traveling magic show. Although Joe had been “about the animals” in the beginning, as time passed, according to Joe’s ex-boyfriend John Finlay, fame and profit monopolized his thinking. Joe’s niece, Chealsi Putman, who helped out at the zoo for years, noticed the same evolution. “It’s like he’s seen dollar signs,” Putman told me. “He figured out a way to make money and ran with it.”

Not all big cat owners are similarly motivated. For some, it’s a grossly misplaced desire to help an endangered species — not realizing that big cats bred in the U.S. are hybridized mutts that have no genetic worth for wild tiger conservation. For others, like 54-year-old Deborah Pierce, the motivation is something more akin to love, or infatuation. Pierce started small, rehabbing injured wildlife at her house and volunteering and working at a local veterinary clinic and zoo after she graduated from high school. But helping lion keepers wasn’t enough to satisfy Pierce. “I wanted one of my own to just spend time with,” she said.

Pierce was encouraged when she learned that at the time her home state of South Carolina had no laws preventing her from owning a big cat. She talked her husband into helping her construct a double-fenced pen on their secluded, wooded property. She easily found a dealer on the internet selling lion cubs for $1,500 — like Nova, “picture babies” that were too large for cub petting by the time of sale — and arranged to purchase a female cub. “I could afford her easier than I could afford a new bulldog,” Pierce said. She named the lion Elsa, and a few months later, she got Charlie, a baby cougar, to keep Elsa company.

That was 12 years ago. Pierce’s perspective has since changed. She’s emptied her savings account on her cats. They eat $5,000 worth of meat a year and the veterinary bills run around $10,000 annually. Last year, the county hit her with an $1,100 fine for not having the proper paperwork. (South Carolina started regulating big cats in 2018.) Pierce no longer has time to ride horses, her other great love, and her husband left her in 2016, breaking not only her heart, she said, but also Charlie and Elsa’s. She’s put a dream of moving out to Arizona on hold as well. State laws there strictly regulate private ownership of big cats, and finding a sanctuary where Elsa and Charlie could stay has proven too difficult. “They’re my best friends,” Pierce said, “but if I had it all to go over again, I wouldn’t have gotten them.”

At this point, Pierce has resigned herself to the long haul, perhaps as many as another eight years given the lifespan of captive big cats. “I just want to be able to give Elsa and Charlie a happy life,” she said. “Their happiness is more important than mine, in my eyes.”

A month after I visited Pierce, she emailed with bad news. Charlie had died in surgery. “His heart was still beating, but he wouldn’t breathe when the oxygen came off,” she wrote. “So, we let him slip away.” Elsa, she says, has been inconsolable, and Deb blames herself for not bringing Charlie to the vet earlier. The bill for Charlie’s last visit, which totaled $4,800, even after the vet gave Pierce a significant discount, has only added to her stress. “I just hope nothing happens to Elsa before money is available again,” she says. “That’s my number one worry right now.”

* * *

The modern exotic animal craze traces back to the ’70s and ’80s and a phenomenon called zoo babies. Each spring, interstate signs and TV commercials featured photos of blue-eyed, squealing balls of fuzz debuting at major zoos around the country, an irresistible marketing lure for families that turned out to snap photos and cuddle the newest arrivals. Zoo babies were among the industry’s number one moneymaking programs, and tigers were always the biggest draw. As an added bonus, zoos advertised these activities under the guise of conservation. “You’d get your T-shirt, get your picture taken, and you’d walk away feeling like you’ve saved the world — you’ve saved tigers,” Harrison said.

But there was a problem, and Harrison, who worked as an exotic animal veterinary assistant as a teenager in Ohio, noticed it. There were lots of zoo babies but no zoo adolescents. When Harrison eventually began asking the staff about what had happened to last year’s tiger cubs, he’d get vague answers about the animals being traded off to different zoos. To Harrison, that math didn’t add up: Even the largest zoos around the country had only two or three adult tigers. But zoos annually paraded hundreds of babies out for pictures and play sessions.

Harrison eventually learned the dark truth: After the cubs reached a certain age they became “zoo surplus” and were sold at exotic animal auctions to private buyers. These auctions were raucous events, attended mostly by veteran wildlife keepers and professional breeders that zoos relied on to supply their collections. Harrison attended a few and noticed the same employees who weeks earlier had been talking up the conservation value of the zoo’s tiger babies, holding cub after cub up by their armpits to sell to the highest buyer. The whole scene was commonplace at the time. “No one thought anything of it,” Harrison said.

The zoo baby phenomenon led to a surge in private big cat ownership. In the 1990s, according to Harrison, wildlife-related television spread the idea of owning a pet tiger to a much wider audience. Jack Hanna types bottle-fed cubs and paraded tigers on leashes on talk shows. The predators appeared no more dangerous than a golden retriever. “It was like somebody flipped a switch on,” Harrison said. At the time, Harrison was the lone police officer in Ohio who could handle big cat emergencies; he suddenly went from getting a couple calls a year to getting more than 100. After removing an unruly pet from someone’s property, he’d ask people why they thought it was a good idea to own a lion or tiger. Many responded it was because they’d seen it on TV. Harrison started calling it the Steve Irwin syndrome.

Jack Hanna holds two Bengal Tiger cubs that were born and bred in captivity during a groundbreaking ceremony at the Dallas Zoo in 1998. (AP Photo/Tim Sharp)

That turns out to be an apt diagnosis. According to research conducted by scientists at Duke University, seeing a wild animal in an unnatural, human setting — a chimpanzee drinking out of a baby bottle or sitting through a talk show interview — makes people less likely to donate to a conservation organization that aids that species and more likely to think the creature in question would make a great pet. According to Kara Walker, now a behavioral ecologist at North Carolina State University and lead author of the research, published in 2011 in the journal PLOS One, this also extends to people’s thought process after an encounter with a cub, which might go something like: Look at this cuddly tiger! I got to pet it for 20 minutes and it licked my hand and now I can have a tiger, too!

Enterprising private exotic animal owners capitalized on the moment. They realized they could make a killing holding their own cub petting events at malls, fairs, and roadside zoos, which compounded an already vicious breeding pattern. “I call it the breed and dump cycle,” said Nasser, the Michigan State law professor. That cycle is largely responsible for the proliferation of tigers throughout the U.S., and by the middle of the last decade, the most notorious of all the breed-and-dump outfits belonged to Joe Exotic.

But cub-petting events weren’t enough for Joe. Concerned with fame and fortune, he plotted ways to grow his online following and commercialize the business. He started selling Tiger King–branded candy, apparel, and condoms. He also kept zoo costs down by euthanizing sterile or defective tigers and turned donated animals that weren’t moneymakers — especially emus — into cat food. During regular inspections of Joe’s zoo, the USDA cited hundreds of American Welfare Act violations. The agency conducted four investigations, including one that looked into the deaths of 23 tiger cubs from 2009 to 2010. (As an endangered species, tigers cannot be killed unless there is a legitimate reason, such as ending the life of a sick tiger.) Animal rights groups such as PETA conducted their own covert investigations, revealing what they claimed was gross abuse — dead and dying animals, extremely crowded cages lacking basic necessities such as water, and untrained staff who routinely abused animals. In retaliation, Joe launched social media attacks and filed dozens of contrived police reports claiming his accusers were the ones who were breaking the law.

For years, Joe’s strategy worked: Profit off cubs. Evade his enemies. Skirt the law. It probably would’ve continued to work had Joe’s path not collided, as he once put it, with “some bitch down there in Florida.”

* * *

Carole Baskin in 2017 walking the property at Big Cat Rescue, a nonprofit sanctuary committed to humane treatment of rescued animals, often coming from exploitive for-profit operations. (Loren Elliott/Tampa Bay Times via AP)

Vultures circle overhead as Carole Baskin and I make our way along a secluded stretch of the Upper Tampa Bay Trail, about 15 miles outside of downtown Tampa. A spring breeze flutters her waist-length blond hair and blows through the thick surrounding brush of oaks and palmettos. Despite the blue sky and sunshine, the trail is empty. The only sound is the rustle of leaves and crunch of Baskin’s leopard-print boots on the pavement. It was this trail, Baskin explained to me, on which she regularly bikes to work, that a hitman had identified as a place to take her out.

Baskin is arguably the most well-known activist in the country campaigning against big cat ownership. She also takes in unwanted exotic cats at Big Cat Rescue, her sanctuary in Tampa, which currently houses 66 cats belonging to 11 different species. It’s one of the few places in the U.S. capable of providing these animals with a safe, reasonably good life in captivity.

Like Harrison, Baskin used to be part of the problem. A pivot from big cat owner to big cat conservationist is a common story among advocates in the field. Baskin stumbled into owning an exotic cat in the early 1990s at the age of 31. She and her ex-husband, Don, worked together in the real estate business. They used llamas to mitigate the brush on the Florida properties they sold, and the easiest place to get a llama was at an exotic animal auction. At one memorable event, a man seated next to Baskin bid on a baby bobcat. Baskin couldn’t help but lean over and whisper: “When that cat grows up, she is going to tear your face off.”

“I’m a taxidermist,” the man replied. “I’m just gonna club her in the head in the parking lot and make her into a den ornament.”

Baskin was horrified. Don outbid the man and they brought home the 6-month-old kitten, which Baskin named Windsong. As Windsong grew, the bobcat terrorized Baskin’s daughter and the family’s German shepherd. The solution, Baskin decided, was to get Windsong a playmate. Don found a guy in Minnesota who agreed to sell them a bobcat kitten. Turned out, the man was a fur farmer; Baskin and Don came back from that trip with 56 bobcat and lynx kittens — everything the farmer had for sale. The following year, they returned to rescue the 28 adult cats, too.

With their home overrun by exotic cats, Baskin and Don transformed a nearby 40-acre property they owned into a sanctuary, albeit with misguided tourism and breeding components. They called it Wildlife on Easy Street. They amassed a collection of at least 150 exotic cats of 17 species. For $75 a night, visitors could share a small cabin with a bobcat, cougar, or serval. Baskin started breeding half a dozen big cat species, including ocelots and leopards. Pre-internet, all Baskin’s information came from breeders and dealers, who had their own motivations. “They were saying, ‘Oh, you should breed these animals because they’re endangered and the zoos don’t know what they’re doing and they’re going to disappear from the wild,’” Baskin said. “So, we thought, well, that’s something we could definitely do to help save the cats.”

But people who bought kittens from Baskin often returned the cats after they grew up. Once, a Siberian lynx — an animal Baskin swore she recognized from when it was young — showed up at auction. People started donating cats to Baskin’s sanctuary by the dozens. Some years, she turned away hundreds of animals due to a lack of space. Around the same time, Baskin started attending conferences held by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, where she learned a few hard truths. None of these cats had any conservation value for their species. In fact, Baskin realized big cats had no business being bred and kept as pets at all.

In 1997, Baskin pulled a 180. She stopped breeding and began spaying and neutering all of her animals. She started enforcing a new rule in 2003: Big Cat Rescue, her rebranded sanctuary, would take any unwanted tiger, lion, savannah, or whatever else, but in return the owner had to sign a contract forfeiting their right to own a big cat. “We’re the only place that absolutely insists that if you’re going to dump an animal here, you are never going to own another exotic cat,” Baskin said.

The contracts were a good start, but Carole had an even bigger goal in mind: ending all big cat ownership. Critical to realizing that vision is Howard Baskin, a businessman from Poughkeepsie, New York, who Carole met at an event at the Florida aquarium in 2002. (Baskin’s previous husband walked out the door one day and was never seen or heard from again — though she was questioned, no evidence was ever found linking Baskin to his disappearance.) A lifelong bachelor with a Harvard MBA and a law degree from the University of Miami, Howard appears in many ways Carole’s opposite. Carole dresses like a Woodstock attendee and carries herself with the breezy grace of a dancer. Howard trundles along, turtle-like, in dad-style khakis with a cell phone holster. But they make a good team. Howard handles the administrative and legal duties and Carole focuses on advocacy. “On our honeymoon, we wrote a 25-year plan to stop the big cat abuses that bad guys hold dear,” Carole said.

Carole and Howard started by setting up a Google alert for cub-petting events around the country. Baskin would email the venues explaining the downsides of cub petting and asking them to cancel the event, and if they did not respond, she would then direct her hundreds of thousands of social media followers to flood the venues with emails explaining the downsides of cub petting. One by one, malls began to call off the events. (Fairs proved more impervious to the bad PR.) Baskin homed in on the primary players in the exotic cat world and publicized her findings on 911animalabuse.com, a website she created. One individual stood out among all the breeders: a guy with a dozen different aliases, but whose cub petting photos always included the same motley group of heavily tattooed, pierced, longhaired workers. It was Joe Exotic’s crew.

* * *

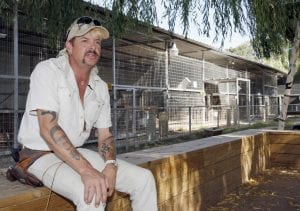

Joseph Maldonado in 2013, answering a question during an interview at the zoo he then ran in Wynnewood, Oklahoma. (AP Photo/Sue Ogrocki, File)

As Baskin ramped up her efforts, Joe’s profits plummeted. In retaliation, he launched a smear campaign against Baskin’s nonprofit. He renamed his cub-petting show Big Cat Rescue Entertainment and designed a near-identical copy of Baskin’s Big Cat Rescue logo. The Baskins sued Joe in 2011 for copyright infringement. Joe countersued, but those claims were tossed out by a judge. Joe eventually agreed to a consent judgement north of $1 million, which he had no intention of paying. He did everything he could to obscure his money, changing the name of his zoo and transferring assets to an account in his mother’s name. Joe also made a series of increasingly unhinged videos posted on social media threatening Baskin’s life. One featured an effigy of Baskin. Another depicted Baskin’s head in a jar, Silence of the Lambs–style.

In 2015, Baskin got a call from a woman who said Joe had inquired with her then-husband, who she said was a former military sharpshooter, about hiring her husband to kill Baskin. Nearly two years later, Baskin received a similar warning from a woman named Ashley Webster, an aspiring wildlife biologist from Colorado who had just started working at Joe’s park. In a deposition, Webster recalled Joe saying “something along the lines of he’d give me a few thousand dollars to go to Florida and put a bullet in [Baskin’s] head.” Carole and Howard reported the incidents to police, but nothing seemed to come of it.

Unbeknownst to the Baskins, the FWS had launched an investigation of Joe and his zoo in 2016 for potential animal trafficking violations. The saga, which has been detailed at length in various news reports, involved an FWS agent convincing a man named James Garretson, who’d done big cat business with Joe in the past, to become a government informant. Garretson agreed to attempt to arrange a meeting between Joe and an undercover FBI agent posing as a hitman. At the outset, what the feds learned was that Joe already had his own scheme in the works: He planned to hire Allen Glover, a man from South Carolina who’d been convicted of assault, for the job.

Glover was a longtime associate of a man named Jeff Lowe, who’d done business with Joe and shortly after started hanging around the Tiger King and his world. Joe, who was under the impression that Lowe was wealthy, made his new friend the co-owner of the zoo’s land, along with his mother. In exchange, Lowe, according to a deposition, said he would pay a portion of Joe’s mounting bills at the zoo and let Joe run the park as usual. “The whole thing was to put the zoo in his name so Carole couldn’t get it,” Joe told me. But Lowe had other plans. In a May 2018 deposition, Lowe admitted that he was interested in the zoo for himself.

According to Glover, who testified at Joe’s trial, he and Joe settled on a $5,000 down payment for the hit on Baskin and discussed other details such as what weapon to use. Glover said that Joe eventually gave him $3,000 cash and a cell phone loaded with pictures of Baskin. But during his two days on the stand, Glover claimed he’d always intended to take the money and run. For his part, Joe denies giving Glover the phone, and said that Lowe was the one who instructed him to pay Glover. (Lowe declined multiple interview requests for this story.) Glover did travel east, but in court he said he only made it as far as an unknown beach in Florida, where he partied most of the money away in a single night. Glover claimed that it was not his intention to kill Baskin in Florida, but rather to warn her that Joe wanted her dead.

Meanwhile, in December 2017, Joe agreed to Garretson’s proposed meeting with the undercover FBI agent. The agent quoted Joe a $10,000 fee for the hit. The two agreed to a rough outline of a deal, but Joe never followed through. Instead, in June, without notice, Joe and his new husband, Dillon Passage, loaded up four dogs, two baby tigers, and a baby white camel, and took off. (Joe’s previous husband, Travis Maldonado, accidentally shot and killed himself in October 2017.) “Joe Exotic, as far as I was concerned, was dead,” Joe told me. He was going to create a new life with Passage.

Joe and Passage left Oklahoma and headed east, eventually landing in Gulf Breeze, Florida. On a sunny September morning, Joe pulled up to the local hospital. He planned to walk in and apply for a job. Instead, unmarked cars surrounded him. U.S. marshals jumped out, guns pointed, yelling at Joe to get on the ground.

Lowe had indeed been working with federal agents since as early as June. Less than a month before Joe’s arrest, Lowe bragged on Facebook that he’d been “setting [Joe’s] ass up for almost a year.” And it seems Lowe got what he wanted. He and his wife, Lauren, now run Joe’s old zoo, where they continue to churn out cubs for playtimes. The nursery lineup recently featured Nova, the rambunctious tiliger who bit my producer.

Jeff Lowe and Lauren Dropla with Faith the liliger at their home in 2016 inside the Greater Wynnewood Exotic Animal Park in Wynnewood, Oklahoma. (Ruaridh Connellan/BarcroftImages / Barcroft Media via Getty Images)

* * *

This past March, journalists from around the country descended on downtown Oklahoma City for Joe Exotic’s trial. Garretson and Glover testified against Joe. Joe’s ex-boyfriend John Finlay testified too. Joe took the stand at the end of the seven-day affair. He said he never intended for anyone to kill Carole Baskin and claimed to have known that Garretson, Glover, and Lowe were conspiring to take him down. He said he played along to better understand their plan and gather evidence he could use against them. The jury deliberated for less than three hours, then found Joe guilty on all charges, including illegally killing five tigers and illegally transporting endangered species across state lines. In January, a judge sentenced Joe to 22 years in federal prison. In a Facebook post, Joe maintained his innocence and said he plans to appeal.

Nasser hopes that Joe’s conviction triggers the beginning of what she calls “a long-overdue Blackfish moment for captive tigers,” referring to the popular documentary that exposed problems with the sea-park business’ treatment of orcas and led to numerous SeaWorld boycotts. Pending any appeals, the Baskins and other activists believe the Tiger King’s downfall could topple the industry. They hope to use the momentum and notoriety of Joe’s case to usher in sweeping legal reform of big cat ownership in the U.S.

Baskin has been pushing for this type of reform since 1998, when she began working on what’s called the Captive Wildlife Safety Act, a federal bill unanimously voted into law in 2003 that barred the sale of big cats as pets across state lines. Loopholes in the law, however, have rendered it largely ineffective. She and Howard — along with major nonprofit groups such as the Humane Society and the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) — have been pushing a new bill, the Big Cat Public Safety Act. First introduced in 2012, the legislation would ban all public contact with big cats, including cub petting, and would require all big cat owners to register their animals. Howard hired a top Republican lobbying firm in 2014 to work with Harrison to champion the bill — not for its conservation clout, but on its pubic safety merits. Senator Susan Collins signed on to the bill last November, the first republican cosponsor. Three other Republican senators, including Richard Burr of North Carolina, have since joined Collins. The registrations would provide officials with valuable insight into who owns what and where — potentially life-saving information in the event of, say, a tornado blowing through a tiger park. The ban on cub petting, though, is the most important part of the bill, as proponents believe it would disincentivize the breeding of big cats.

Last year, the bill made it out of the Committee on Natural Resources in a bipartisan vote and could soon head to the House floor, where it has broad support. “Law enforcement has enough problems trying to protect the public without having to run into a house where there might be a tiger,” said Harrison. Dozens of Republican lawmakers support it — a party full of politicians, who, Harrison said, for the most part “don’t give a crap about cats.”

For now, though, cub petting remains a lucrative industry. According to data compiled by a team of New York University researchers in 2016, at least 77 facilities across the country allowed interactions with exotic animals (about a quarter of those were with big cats). In a follow-up study in 2019, which focused specifically on tiger petting, those same zoos were still open. One operation in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, run by Bhagavan “Doc” Antle, charges up to $339 per person for tours and cub-petting sessions. Supporters of the Big Cat Public Safety Act believe that ending cub petting would go a long way toward stopping the trade of big cats altogether. “Without ending public contact, you’re not going to have sufficient incentive for all the fly-by-night exhibitors to stop breeding,” said Nasser.

The new protections would extend to smaller species such as jaguars and even unnatural hybrids like Nova. They’d also apply to accredited zoos. While the zoo baby phenomenon is no longer as rabid as it once was, not all zoos have ended the practice of animal meet-and-greets. The Nashville Zoo provides clouded leopard cubs for zoo fundraisers and media events (zoo officials say that play and petting sessions are not allowed), and the Dallas Zoo recently held a cheetah photo op session for the Dallas Stars (zoo officials point out none of the Stars were able to pet the cheetah, however).

Limiting and eventually banning big cat ownership in the U.S. would almost certainly be a boon for the species worldwide. Fewer than 4,000 tigers survive in the wild today. But they are farmed by the thousands in China, Laos, and other Southeast Asian countries where big cat parts are sought after as erroneous medicinal remedies and status-touting commodities. Tiger bone wine, in particular, is considered a cure-all tonic, a virility booster for men, and a coveted, favor-winning gift for superiors, elders, and relatives.

Tiger bone is banned in China, and it’s illegal to trade big cats and their parts in Vietnam and elsewhere in Southeast Asia. But there’s a robust black market for tiger bones, skin, teeth, and claws — and farmed tiger parts keep demand for these items alive, perpetuating poaching. The U.S. government considers closing tiger farms integral to saving wild tigers, but when State Department officials try to negotiate this point with foreign diplomats — especially those from China — they’re often told to clean up their own mess first. “When I talk to government leaders about tiger farming in many of the Asian countries, quite often they ask me, ‘What about tigers in the U.S.? What role do the tigers in private backyards in the U.S. contribute to wild tiger conservation?’” said Grace Ge Gabriel, IFAW’s Asia regional director. “Literally, I am speechless. I don’t have an answer.”

A tiger named Seth rests above a pond at Big Cat Rescue in 2017. (Loren Elliott/Tampa Bay Times via AP)

* * *

After I first contacted Joe following his trial, we spoke several times over the next few months. He liked to talk, only cutting off our calls if another person in the prison needed to use the phone. Joe never admitted any wrongdoing when it came to Baskin; rather, he was eager to defend his innocence. Multiple times he told me, “That whole mess was nothing but a setup.”

Joe did cop to something else, though. He said being locked up in jail had made him realize he’d mistreated the animals all those years, depriving them of their freedom and robbing them of their dignity by keeping them behind bars. Joe told me he regretted having done that. “Now that I have nothing to do besides sit in a cell with no TV, no radio, no nothing, I know exactly what I did to those [animals],” he said. “We can all be drove crazy by doing nothing.”

To make amends, Joe told me he plans to create a new zoo when he gets out. This one without any cages. Just tigers roaming free.

You can listen to our four-part “Cat People” podcast series on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Rachel Nuwer is an award-winning freelance journalist who reports about science, travel, food and adventure for the New York Times, National Geographic, BBC Future and more. Her multi-award winning first book, Poached: Inside the Dark World of Wildlife Trafficking, was published in September 2018 with Da Capo Press.

Editors: Mike Dang and Chris Outcalt

Illustrator: Zoë van Dijk

Fact checker: Matt Giles

Copy editor: Jacob Gross