On October 1, we received a call from the owner—a 55-year-old diabetic with heart problems who was recovering from injuries sustained in an auto accident seven months earlier. She had just decided that the “zoo” was not a fit home for her chimps, and was in a panic because the zoo owner—angered by her change of mind—knew that the animals’ living quarters had not been cleaned since her accident. She feared that he would turn her in to the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, which might confiscate her “babies.” (She brought the chimps into Georgia in 1977, and was “grandfathered in” when the state later enacted its Exotic Animal Law barring the private possession of certain dangerous primates, carnivores, reptiles, etc.)

After learning that these five animals—who ranged in age from 24 to 28 years old—were bedded on newspaper in two 10 x 10-foot cubicles, we convinced the owner to allow us to clean the enclosures and do some needed repairs. We loaded our pressure washer, cleaning equipment, and Rachel Weiss—a newly hired former Yerkes caretaker—and drove the 350 miles to Dahlonega, Georgia, on October 5.

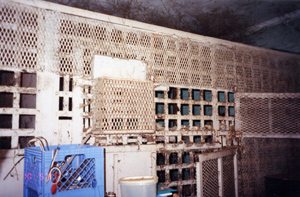

The building’s two 10 x 10 cubicles were separated by a 5 x 10-foot holding area. The shift doors hadn’t been opened in so long they were corroded shut. Late in the day, we were finally able to pry them open enough to allow the two chimps on the right end to join the three on the left. That gave us access to the chimp living space and a chance to assess the work ahead of us. Newspaper, old food containers, and waste littered the small space. To make room for themselves, the chimps had learned to push everything against the front walls of their cells, forming a mass in each cubicle that was 4 feet wide, 3 feet deep, and 10 feet long.

We cleaned, mopped, and installed drain covers that could be removed for cleaning. The rest of the visit was spent installing iron strap reinforcements on the building’s exterior to prevent the chimps from further dislodging several loose cinder blocks. We also began talking to the owner about finding another home for the chimps, and left with a promise that she wouldn’t continue to house the dogs in the chimp area.

Two days later, she suffered a heart attack and was hospitalized. By phone, she indicated she was terrified that DNR would confiscate her animals. She pleaded with us to take ownership of them, and we had her sign a donation agreement. The chimps could now be evacuated—but the question was, to where?

We contacted Dr. Sarah (Sally) Boysen, with the Chimp Cognition Lab at Ohio State University, who had successfully rescued several privately owned chimpanzees. After exhausting other possibilities, she called colleagues at the Yerkes Regional Primate Center in nearby Atlanta. They graciously agreed to temporarily house and quarantine the chimps at their field station in Lawrenceville, a short drive from Dahlonega. They further offered their veterinary services and a van to immobilize and transport the animals.

While these negotiations were underway, the owner returned home from the hospital. Now, we’d need to get her cooperation. She finally agreed that the animals could be moved, but insisted it must be done on Thursday, November 13. As we headed for Georgia on November 11, Sally Boysen called to say that Yerkes would not have a vet available that day, but the facility was otherwise ready to accept the chimps. The design of their cages would not allow us to transfer the chimpanzees without anesthetizing them, and while we had them “down” we wanted to perform complete physicals, as they had not had veterinary care in nearly 20 years. We needed to find a qualified veterinary team, and quickly.

We called zoos in Atlanta and Knoxville, to no avail. In desperation, we called Dr. George Rabb, the director of the Brookfield Zoo in Chicago, hoping he could persuade a local zoo to help us. To our astonishment, we received a call back within the hour offering the services of a Brookfield vet, an assistant, and any necessary equipment. Dr. Tom Meehan and Vince Sodaro flew to Atlanta the next evening, and we met to plan our strategy for the move.

We combed the United States, visiting sanctuaries and exploring options in an attempt to find another permanent home for the Georgia chimps. What we found was discouraging, to say the least. With LEMSIP having sent almost 100 chimpanzees to U.S. sanctuaries prior to closing in late 1997 (including the seven which we took in), nearly every facility was full.

We contracted for an outdoor enclosure and made plans to transport the five chimps to Kentucky. Although we missed our deadline for moving them out of Georgia, Yerkes agreed to a time extension while we readied temporary caging for them. Finally, in the fall of 1998, the five chimps arrived at the Primate Rescue Center. And on July 6, 1999, they moved through our tunnel system to their new outside enclosure. After years of confinement in a miserable dark bunker, they were free to enjoy the fresh air and sunshine.